|

HAROLD LLOYDSAFETY LAST By Matt Barry |

Matt Barry is a film enthusiast, film maker and film historian. His contributions to our site are always welcome.

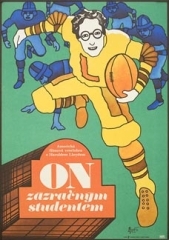

With Safety Last, Harold

Lloyd scaled the heights of the

artistic possibilities of the silent film medium,

and gave silent comedy perhaps its most iconic moment: that of the

bespectacled, straw-hatted go-getter hanging from the side of a

skyscraper on the second-hand of a large clock, dangling over a busy

street.

With Safety Last, Harold

Lloyd scaled the heights of the

artistic possibilities of the silent film medium,

and gave silent comedy perhaps its most iconic moment: that of the

bespectacled, straw-hatted go-getter hanging from the side of a

skyscraper on the second-hand of a large clock, dangling over a busy

street.

Lloyd made better films than

Safety Last: The

Kid Brother

is probably the strongest from a narrative standpoint; The Freshman

provides a stronger character arc; and it would be hard to top Why

Worry? for sheer number of clever gags. But what makes Safety Last, and

especially its “human fly” sequence, so iconic is precisely the fact

that it demonstrates the art of silent comedy that was so totally

unique to the medium.

Lloyd got the idea for the building

climb when he

observed a “human fly” scaling the side of a building in Los Angeles.

He recruited that climber, Bill Strother, to act in the film. Lloyd had

worked in “thrill comedy” before, most notably in his short films High

and Dizzy (1920) and Never Weaken (1921), the latter with its memorable

sequence in which Harold, believing he has successfully committed

suicide, is lifted up on his office chair and out through the window by

a girder beam on a crane. As he believes he is ascending to Heaven, he

gets a rude awakening when he looks down to see the city streets below

him! Although “thrill comedy” wasn’t new to Lloyd, he would take it to

new heights in Safety Last.

In many ways, the plot of Safety Last

seems to exist

solely as a means of getting Harold up on that building. The plot is

set up in the opening scene, when Harold’s girlfriend (played by

Lloyd’s wife and long-time leading lady, Mildred Davis) tells him to go

to the city and make good. He finds work as a department store clerk,

and, desperate to climb the ladder of success, pitches a publicity

stunt in which a “human fly” (played by Bill Strother) will scale the

side of the department store. Complications ensue on the big day, when

Strother is forced to flee from a policeman, and Lloyd is forced to

climb the building himself.

Much has been written about the lengths

to which

Lloyd went to achieve the effect of being as high up on that building

as he appears to be. Walter Kerr, in The

Silent Clowns,

notes that the building itself was located on a hill which, when

combined with the careful placement of the camera, gave the illusion of

a being at a much steeper angle than it actually was. Additionally,

Lloyd placed a mattress below him in order to break his fall should he

drop.1 Regardless of the means used to create

the illusion,

and the precautions taken to lessen the risk, Lloyd really demonstrates

his incredible physical abilities in this sequence, displaying an

astonishing degree of creativity in finding new ways to keep the

audience in suspense as he scales the building. Despite the length of

the sequence - more than a third of the film’s running time 2

- it never grows dull or repetitive. In This is Orson Welles, Welles

said of Safety Last’s “human fly” sequence: “As a piece of comic

architecture, it’s impeccable. Feydeau never topped it for sheer

construction.”3

The climb is a perfectly structured

piece of comic

filmmaking. In Film as Art, Rudolf Arnheim writes about selective

camera placement as an example of “how the various peculiarities of

film material can be, and have been, used to achieve artistic effects.”4

In this respect, Safety Last is an excellent example of the artistic

effects made possible by the placement of the camera in heightening the

effects of thrills and danger that are so essential to the comedy.

The opening sequence of the film gives another example of this

technique at work. We first see Harold in close-up, standing behind

bars. In the background is a noose, and a uniformed official stands

near him. We then see his girlfriend saying goodbye to him, with tears

in her eyes. The viewer assumes that Harold is in prison, about to be

led to his execution. However, the next shot-a wide shot-reveals that

Harold is merely waiting at the gate of a train station; the uniformed

official merely a conductor; the noose a mail catcher, and so on. Aside

from serving as a bit of dark humor, it also provides another example

of the kind of tricks Lloyd played on the audience by selectively

showing only parts of the entire scene. This cinematic deception also

hints at the character deception that Harold must engage in throughout

the film: hiding with his roommate in coats hanging on the back of a

door in their apartment in order to dodge the landlord; posing as the

store manager to impress his girlfriend when she makes a surprise visit

to see him at work; and of course, being forced to play the part of a

“human fly” in order to save his job at the department store. In

addition to the suspense provided in the building climb sequence, there

is also a great deal of suspense in wondering how long Harold will be

able to pull off his charade in posing as the department store manager.

Lloyd seems to be commenting on the dizzying heights of success to

which his character is expected to climb, and the illusion, based on

deception, that could be shattered at any moment.

The opening sequence of the film gives another example of this

technique at work. We first see Harold in close-up, standing behind

bars. In the background is a noose, and a uniformed official stands

near him. We then see his girlfriend saying goodbye to him, with tears

in her eyes. The viewer assumes that Harold is in prison, about to be

led to his execution. However, the next shot-a wide shot-reveals that

Harold is merely waiting at the gate of a train station; the uniformed

official merely a conductor; the noose a mail catcher, and so on. Aside

from serving as a bit of dark humor, it also provides another example

of the kind of tricks Lloyd played on the audience by selectively

showing only parts of the entire scene. This cinematic deception also

hints at the character deception that Harold must engage in throughout

the film: hiding with his roommate in coats hanging on the back of a

door in their apartment in order to dodge the landlord; posing as the

store manager to impress his girlfriend when she makes a surprise visit

to see him at work; and of course, being forced to play the part of a

“human fly” in order to save his job at the department store. In

addition to the suspense provided in the building climb sequence, there

is also a great deal of suspense in wondering how long Harold will be

able to pull off his charade in posing as the department store manager.

Lloyd seems to be commenting on the dizzying heights of success to

which his character is expected to climb, and the illusion, based on

deception, that could be shattered at any moment.

Safety Last was the second-to-last film

Lloyd made

with producer Hal Roach, whom he’d been working with virtually ever

since they entered films together in the early 1910s. They parted ways

in 1923, with Lloyd setting up his own independent production for

release through Pathe (and later Paramount). “Thrill” comedy would

remain a part of Lloyd’s work, but he developed his craft toward an

increasingly character-oriented approach that would culminate in films

like The Freshman and The Kid Brother. The memorable chase sequences in

Girl Shy, For Heaven’s Sake and Speedy, not to mention the exciting

fight in the hold of a ship in The Kid Brother, are examples of the

“thrill” element he never totally abandoned. He would never again

create a “thrill” sequence as effective, thrilling and funny as the

building climb from Safety Last, however. His attempt in his second

talkie, Feet First, pales in comparison, partly because the situation

lacks the narrative drive of the earlier film, and also because the

addition of sound subtracts from the overall experience, emphasizing

the danger Harold is in and diminishing the comedy. In his final screen

appearance, in Preston Sturges’ The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947),

Harold once again finds himself on the ledge of a tall building, except

this time the “thrill” effect is totally neutered by the fact that he’s

clearly in front of a process screen.

Safety Last remains one of Lloyd’s most

popular

films; its image of Harold hanging from the clock has been copied and

imitated, but never equaled. A masterpiece of comic construction,

driven by a strong, logical flow of gags, character and narrative, it

is a perfect representation of the art of silent

comedy.

Endnotes:

1. Walter Kerr, The Silent Clowns.

(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1975), 198.

2. Joe Franklin, Classics of the

Silent Screen. (Seacaucus, NJ: The Citadel Press, 1959), 44.

3. Orson Welles, quoted in Jonathan

Rosenbaum, ed. This is Orson Welles. (Cambridge, MA: DaCapo Press,

1998), 38.

4. Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art.

(London: Faber and Faber Ltd., 1958), 38.

Copyright © Matt Barry, 2010. All Rights Reserved. Used by Special Permission.