THE NAVIGATOR

(1924)With Buster Keaton, Kathleen McGuire, Frederick Vroom

Directed by Donald Crisp and Buster Keaton

Silent, Black and White

Reviewed by JB

Buster Keaton may be the most admired of the great silent comedians

today, but in his own time, he generally ran third in terms of box

office and popularity, behind Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin. Some of Keaton's greatest films, such as THE GENERAL and STEAMBOAT BILL, JR.,

were huge box office failures. What was it about Keaton that eventually made audiences turn away in

the 1920s?

Buster Keaton may be the most admired of the great silent comedians

today, but in his own time, he generally ran third in terms of box

office and popularity, behind Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin. Some of Keaton's greatest films, such as THE GENERAL and STEAMBOAT BILL, JR.,

were huge box office failures. What was it about Keaton that eventually made audiences turn away in

the 1920s?

Perhaps we have a clue in what James Agee wrote about Keaton in his 1949 Life Magazine piece "Comedy's Greatest Era":

"He was the only major comedian who kept sentiment almost entirely out of his work, and he brought pure physical comedy to its greatest heights. Beneath his lack of emotion he was also uninsistently sardonic; deep below that, giving a disturbing tension and grandeur to the foolishness, for those who sensed it, there was in his comedy a freezing whisper not of pathos but of melancholia."

That melancholia can be seen in one of the first scenes in THE NAVIGATOR. He arrives at the home of his best girl and asks her flat out to marry him. When she refuses, he takes it in for a second, collects his coat and cane, and walks out. We know he has to be hurting - he tells his butler a long walk will do him good as he heads back to his own home directly across the street - but he doesn't show it on his face. We know how Lloyd or Chaplin would have handled the moment; both were masters of openly showing a broken heart. Keaton remains stone-faced.

The lack of sentiment is in the same scene too. Lloyd usually developed some business whenever he was trying to tell a girl he love him, the most memorable being his stutter in GIRL SHY when he cannot get the worlds "Will you marry me?" out of his uncooperative mouth. The girl, loving Harold, eventually says "I will!" without him ever asking. In Keaton's films, women were more apt to be props or straightmen that true love interests, and Keaton's way of getting laughs with the idea of proposing is minimalistic in its approach. First, after seeing a couple drive by on their honeymoon, he tells his butler "I think I'll get married!" followed by an impulsive and emphatic "Today!". Then, the laugh in his actual proposal comes simply with its abruptness. There is no gag, but there is also no hemming and hawing, no getting down on one knee, no ring, simply a walk into a room and a "Will you marry me?".

It may be a cliché that audiences want to like the people they watch on the screen, but certainly Chaplin, Lloyd and Laurel and Hardy were popular and projected likable personalities. The Marx Brothers may not have wholly likable, but there was much to admire in the way they attacked some of society's prime targets. Still, when they moved to MGM and had their characters softened and their comedy somewhat watered down by producer Irving Thalberg, they had two of their biggest hits in A NIGHT AT THE OPERA and A DAY AT THE RACES. Audiences liked the idea of the Marx Brothers actually working toward something rather than working against everything. W. C. Fields often played a sympathetic henpecked husband with small but important dreams, but even when he played a con artist or layabout, he usually maintained some warm, loving relationship with a daughter or daughter-figure (THE MAN ON THE FLYING TRAPEZE, POPPY, NEVER GIVE A SUCKER AN EVEN BREAK). Other later comedians, like Curly Howard, Lou Costello, Huntz Hall and Jerry Lewis, were essentially overgrown children.

Keaton, however, felt and still feels like a creature from another world. He is not interested in you, nor in your feelings for him. He is interested in the way the world works, and in the ways he can work around the world when it doesn't work. He is the most mechanical, methodical and mathematical of all the great silent comedians. The way he had of setting up a gag, putting every piece in place before springing it, was unmatched by any of his contemporaries. He lived to invent funny business, and audiences initially appreciated that. Yet, perhaps as time went on, audience may have realized Buster was never going to ask them to love him. Maybe they grew wary of the wall he constantly put up in each film, a wall that clearly told them they were on one side and he was on another, and although they were allowed to look, they were not allowed to love, so by the time Keaton made THE GENERAL, now acknowledged as his masterpiece, audiences were no longer content with merely being amused by gags and astounded by spectacle. They needed a hero they could root for, and Buster wasn't it. THE GENERAL, one of the man's most visually impressive films, died at the box office. Ironically, it wasn't until Keaton lost much of his creative freedom and had his character softened at MGM (under Thalberg, like the Marx Brothers later on) that audiences came back to his films. His early talkies, much scorned by fans for wasting Buster's true talents, made more money than many of his silents.

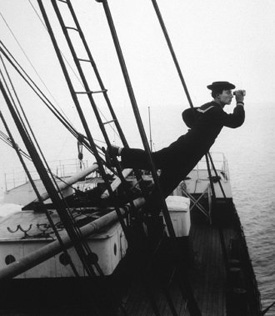

THE NAVIGATOR, one of Keaton's greatest silent films, has all the things you expect from a Keaton comedy:

plenty of gags, large props and sets (in this case, an ocean liner is both), perfectly timed

sequences worked out to the split second, stunts, thrills, a bit of

surrealism (Buster underwater directing fish traffic) and, as always, a

main character whom asks nothing of his audience except "Enjoy our

little funny story!". The film was Keaton's biggest hit so far,

so it is clear that he was well thought of in 1924. However, by

that time, Keaton had only made four feature comedies, Lloyd five, and

Chaplin was still filming his second, THE GOLD RUSH. I suspect that in 1925, that Chaplin film and Lloyd's THE FRESHMAN,

two seminal silent comedies, may have codified the idea in the minds of

audiences that comedy features were more involving when they

had lead character whom they could root for, love and even

pity. Both Chaplin's lovelorn gold prospector in THE GOLD RUSH

and Lloyd's desperate to be popular college boy in THE

FRESHMAN were mocked and ridiculed by other characters in their

prospective films, and driven to a point of complete despair by the

film's plots, making their inevitable triumphs all the more satisfying.

Keaton never asked audiences to root for him or pity him. He

never reached that point of despair, because despair wasn't in him.

When the plots of his films backed him into a corner, he simply assessed

the situtaion and came up with some Rube Goldberg way of working it all out.

He went

about his business (being funny) and hoped you enjoyed the gags and the

story. He rarely made concessions to audience taste, and

when he was forced to, such as in the FRESHMAN-inspired COLLEGE,

audiences didn't buy it. Chaplin and Lloyd did those kind of

things much better.

THE NAVIGATOR, one of Keaton's greatest silent films, has all the things you expect from a Keaton comedy:

plenty of gags, large props and sets (in this case, an ocean liner is both), perfectly timed

sequences worked out to the split second, stunts, thrills, a bit of

surrealism (Buster underwater directing fish traffic) and, as always, a

main character whom asks nothing of his audience except "Enjoy our

little funny story!". The film was Keaton's biggest hit so far,

so it is clear that he was well thought of in 1924. However, by

that time, Keaton had only made four feature comedies, Lloyd five, and

Chaplin was still filming his second, THE GOLD RUSH. I suspect that in 1925, that Chaplin film and Lloyd's THE FRESHMAN,

two seminal silent comedies, may have codified the idea in the minds of

audiences that comedy features were more involving when they

had lead character whom they could root for, love and even

pity. Both Chaplin's lovelorn gold prospector in THE GOLD RUSH

and Lloyd's desperate to be popular college boy in THE

FRESHMAN were mocked and ridiculed by other characters in their

prospective films, and driven to a point of complete despair by the

film's plots, making their inevitable triumphs all the more satisfying.

Keaton never asked audiences to root for him or pity him. He

never reached that point of despair, because despair wasn't in him.

When the plots of his films backed him into a corner, he simply assessed

the situtaion and came up with some Rube Goldberg way of working it all out.

He went

about his business (being funny) and hoped you enjoyed the gags and the

story. He rarely made concessions to audience taste, and

when he was forced to, such as in the FRESHMAN-inspired COLLEGE,

audiences didn't buy it. Chaplin and Lloyd did those kind of

things much better.

Today, I greatly admire all three of the great

silent comedians. For me, Chaplin's films are in a category all their own,

Harold Lloyd's films are the best constructed and the funniest, but Keaton's are always the most fascinating. With

Keaton, laughter is often secondary; just being in the company of

such a person is enough to make the films entertaining.  ½- JB

½- JB